Llama care, management and resources

- Llama FAQ

- Llama literature

- Basic care

- Castration

- Spaying

- About breeding llamas

- Handling young llamas

- Misdirected territorial aggression

- How old should llamas be for training and work?

Fiber from llamas

Llamas

as guardians

Classic performance llamas

Communicating

Our llama family

Just for fun

Cria photos

Training consultation

Performance

llama analysis

What is a classic llama?

In North American llamas, "classic" is first and foremost a coat type:

Classic llamas:

- are distinctly double-coated

- have abundant guard hair over the entire body

- have underwool that molts seasonally and is easily combed out

- are notably sparse-coated (not dense) when kept combed out

When combed out, classic llamas have the appearance of being almost entirely guard hair; the undercoat is only visible at the front of the neck where guard hair is naturally minimal. Two other visual effects of a combed-out classic llama are a trim, almost uniform width compared to leg width and foot placement (rather than the "wide body" look) when viewed from front or rear, and the lack of undercoat at the tailhead produces the visual effect of a rounding of the rump just before the root of the tail; a slight wither contour may also be barely discernable (instead of the "flat topline" look of fleeced llamas).

. . .

short guard hair & smooth leg hair ........... long guard hair & roughened leg hair

The guard hair on a classic llama may be either long or short; the wool fiber beneath is generally about two inches long on both types. Extremely long guard hair (not shown above) interferes with combing out the shedding underwool and is selected against for that reason.

Classic llamas may also have smooth or roughened leg hair. The latter gives the illusion of larger cannon bones, but is of no consequence to performance.

Classic llamas can withstand cold northern winters and all but the most humid, hot climates within the United States when properly cared for (we are told that all types of llamas in humid, hot climates are better off shorn and permitted access to shade, misters and other cooling strategies). In fact, if caretakers in temperate to northern climates make the mistake of shearing a classic llama, they will have a battle on their hands getting that llama through the winter.

Classic llamas also have short neck wool with a distinct "mane" of guard hair; short hair (not wool) on their faces, legs, and ears; and a large "window" of short, smooth hair on either side of their sternum. These latter attributes also sometimes appear in crossbred llamas, and so are not individually definitive of the classic coat type.

Because the classic coat type is of definite advantage to the working llama (something the Quechuans already recognized), most who breed classic llamas select only those that have the physical and mental attributes that make them ideally suited for packing and driving. Unfortunately, some people breed classic llamas irresponsibly, just as some people breed other animals irresponsibly. The predictable result is that not every classic llama is a good packer or harness llama. However, a classic llama who is a rotten performance llama still has a classic coat, and thus is still a classic llama.

Finally, although ears have nothing to do with performance or coat type and maintenance, ears DO define "llama" -- llamas have distinct ear features that produce a shape unique to llamas. Thus, classic llamas also have llama ears: Rounded tips that are positioned above or medial to the medial (inside) ear edge, and not the wild-type spear-shaped ears that terminate in points centered between the inner and outer edges of the ears as in alpacas, guanacoes, and vicuñas.

What ISN'T a classic

llama?

Light wool and "medium wool" (old terminology): These are fleeced llamas. Their undercoat doesn't shed, can't be combed out, and they MUST be shorn. A good rule is (unless you live in the deep south): If the llama is shorn, it is NOT classic! (And a good companion rule is: If the llama is not completely shorn including the neck and legs, the climate is not the reason it must be shorn.) A few of these llamas do shed every second year and can be combed then; they are still not classic-coated. Many (but not all) of these llamas shed their neck fiber, especially on the front, and thus novices are prone to confusing them with classic llamas. (Providing llama shearing and grooming services for a year or so quickly cures THAT notion!) Most of these llamas are crossbreds between one heavily-woolled parent and a nonwoolly parent, either fleeced or classic -- look at both parents and you'll usually see that they aren't even similar.

. . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . .

Both of these llamas would commonly be mistaken for classics ... in comparison to woolly llamas. Any classic llama afficianado would whip out a brush and comb and quicly determine the truth!

The llama on the left is a light wool llama. His fleece does not shed at all and definitely does not comb out. He must be shorn yearly -- sometimes twice a year -- because his dense fleece binds as it grows out and makes him quite upset when touched. He does have visible guard hair and his fleece is short overall, but he's definitely not classic by any stretch of the imagination.

The llama on the right does shed out her neck and her neck has a visible mane of guard hair like a classic llama, but like the light wool llama on the left, her body fleece doesn't shed and definitely doesn't comb out. She would have been called "medium wool" in the early 1990s; today she would be called by many terms, but in the end, the truth is, she is a crossbred and not of any particular breed. She has several woolly ancestors and several classic ancestors; she's inherited some of the characteristics of each.

Neglected classic llamas can be almost visually indistinguishable from light wool and "medium wool" llamas that haven't been shorn.

The first llama (left) is a classic llama. She combed out in two sessions totalling less than 90 minutes. The biggest clue that she might be classic and comb out is the lack of width to her neglected coat despite the extreme matting; however, she might instead have had a very dense, short, two-year-shedding fleece -- lack of width is no guarantee!

The second llama (center) is a long-coated classic llama. He combed out in two sessions totalling about 3 hours. His guard hair is quite long and his coat would be considered "marginal" for breeding for that reason. Still, his "before" photo shows a strong clue that he is classic and will comb out -- the matting is not uniform; much has already fallen out in locations besides his neck. Again, there are no guarantees -- short sections in a neglected coat can also occur when fiber is broken off through rubbing against fencing and such in response to an intense external parasite infestation.

The third llama (right) is a light-wool llama, although he might be considered "medium wool" by some. He had to be shorn, and although his fleece can be brushed, it does not shed completely and he still must be shorn at least every other year. Clues that he is not a classic llama (in his "after" photo) include fluffly neck underwool that stands out and obscures the guard hair instead of shedding off, fluffy wool on top of his forehead, and a matte, fluffy, "cotton candy" appearance to the surface of his fleece after grooming. But, notice that it's not so easy to tell from his "before" photo -- there, the neck fiber isn't as healthy and has partially shed, and the guard hair on the lower neck is showing.

Also notice the evident sheen to llamas one and two (left and center) after grooming, a direct result of the guard hair so prominent in their classic coats -- but completely hidden in their "before" photos, making them harder to distinguish from crossbred llama three (right)

Some llamas are borderline: They can be combed, but it's a lot easier on everybody if they're shorn. In fact, many of these llamas can't be combed anymore after they've been shorn once because their undercoat behaves like a fleece when temporarily deprived of the protection of longer guard hair. These llamas have one or more woolly, light wool, or crossbred ancestors.

As any of these llamas age, their coat consistancy may change enough to allow easier combing, particularly if there is guard hair in the fleece/coat and particularly if they have some classic ancestry -- in fact, some llamas who don't comb at all in their youth may be combable by their mid-teens. BUT ... none of these llamas are true classics.

Two examples of borderline classic llamas -- both comb out, but with difficulty. Although the incompletely-combed llama on the left definitely looks different (a more bulky coat), you'd have a hard time discerning from photos alone that the completely-combed llama on the right does not have a good classic coat.

The llama on the left has a woolly great-grandparent and two other borderline ancestors; the llama on the right has several dense-coated, nonshedding ancestors.

Guanacoes are seasonal shedders, but the coats are dense and resist combing, and the part of the shed that falls off on its own is actually two-year-old undercoat. Guard hair is noticeably less abundant than on classic llamas, especially on the rump; you'll never see a guanaco with the uniform and glossy classic coat. The ear shape is also the wild type and not the unique llama ear.

Nobody considers guanacoes to be classic llamas, but many people who have not owned and cared for guanacoes have no idea how dense and non-combing a guanaco coat is, and incorrectly assume that guanacoes have classic coats just because there's more visual similarity between guanacos and classics than between either one and heavily-woolled llamas.

Notice that, despite grooming, this guanaco retains clumps of fiber that are resisting shedding. Dense coats that fully shed only every two years are a distinct advantage to guanacoes, which normally live in harsh, windy climates (unlike this captive-bred fellow, whose dense coat still protected him well in western Oregon).

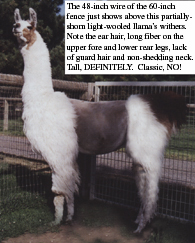

Height is definitely not synonymous with classic llama -- and as you can see, tall llamas come in other types, too.

. . . .

. .

. . . .

. .

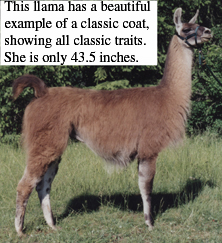

Also, don't make the common mistake of thinking all classics must be tall! In fact, miniature llamas can be bred with a classic coat. Remember that classic is a distinct coat type; that's what makes it a recognizable and separate breed type. Also remember that although classic llamas are usually bred for performance and athleticism, "tall" does not confer those qualities and can even be detrimental to those goals, and that quite a few medium-small llamas (42" to 43.5") do their demanding jobs not just very handily, but exceptionally well.

Genotypic crosses look phenotypically (outwardly) just like classic llamas. However, one parent (virtually always the sire) is not classic, although sometimes it's a grandparent that's to blame for the non-classic genes. Because these llamas are the product of crossbreeding, a significant proportion of more obvious crossbred-type offspring results; some may occasionally even produce a heavily-woolled (fleeced) llama! Results are worst when crosses are bred to crosses.

. . . .

. . . .

Mother (she has a woolly grandparent) .... and her very woolly son . [photos courtesy JNK Llamas]

Another example: Woolly father ... and crossbred but classic-appearing son

Knowledgeable breeders prefer not to breed first-generation genotypic crosses at all if they can help it, and they won't ever breed two first-generation genotypic crosses to each other. They also both minimize the number of genotypic crosses in their herd and pairings, and maximize the number of generations between any nonclassic ancestors and the animals they are actually breeding.

Country of origin, whether of the individual or its ancestors, does not determine coat or fleece type, and thus does not define whether a llama is classic or not. Although most (but not all) imports have been fleeced llamas of varying types, some have been phenotypically classic, and certainly some very fine classic llamas in North American do have an ancestor that was imported from South America in recent history.

There are classic llama breeders who choose not to breed any llama with recent imports in their ancestry, and there are at least as many who have deliberately used one or more recent imports or descendants of recent imports in their breeding program for various reasons.

A few individual llamas who are not true classic type do have substantial physical assests, and so they can occasionally be found in classic llama breeding programs. The most common reason is that there are NO conformational traits that are found exclusively in association with a given coat or fleece type, but some conformational traits are both prized and difficult to come by, making cautious, limited crossbreeding a potentially positive choice. Successful classic breeders will use such llamas very sparingly and make all pairings with these llamas very carefully. However, such llamas and their immediate offspring are not true genotypic classic llamas, and honest breeders are very quick to point this out. The most common non-classic llamas in breeding programs are the genotypic crosses and those llamas you'd never guess weren't ideal classics if you weren't the person who had to painstakingly comb their not-quite-classic coats.

Questions and answers

about classic llamas

Why "classic"?

Webster's defines "classic" in part:

classic \'klas-ik\ adj. 1a: of recognized value: serving as a standard of excellence; 1b : TRADITIONAL, ENDURING

The traditional llamas of South America, called "ccara" by the native Quechuans (and later, llama pelada by the Spanish), had fiber that was both short and coarse. They were used as pack animals, and rarely (if ever) shorn. They were generally larger than the woolly fiber llamas that were later developed from a rather fortunate mutation, although mummified remains show that the ccara llamas were not giants. Their stamina, strength and carrying ability were held to be vastly superior to the woolly fiber llamas.

When llamas were first exported to other countries and climates, the traditional llamas became the dominant type outside South America. Because llamas were kept almost exclusively by game farms and zoos, and they were managed by exotic animal models (hands-off except in cases of extreme illness, and certainly no grooming or shearing). Game farms and zoos also made only the most basic breeding decisions, and so llamas reproduced "on their own," definitely affected by environmental fitness: Fleeced llamas, particularly the woolly fiber llamas, are at an extreme reproductive disadvantage (heavy fiber can prevent intercourse, reduce or completely eliminate viable semen for part of the year, and impair stamina), and even a significant survival disadvantage if not regularly shorn. It is not surprising that classic llamas flourished and later dominated the game farm and zoo populations -- the same traits now valued by North American llama packers for weather protection and stamina made a direct contribution to the classic llamas' survival and comparative reproductive fitness after initial importation in the early 20th century.

So these traditional llama traits have endured despite mechanization in South America and, much later, emphasis on spectacular wool length and quantity in North America. Although the shifting emphasis had resulted in widespread crossing between the traditional working and newer fiber types, there are llamas on both continents -- as well as in other countries -- that still fit the traditional profile.

In North America, the term classic llamas was adopted in early 1991 after years of being lumped with "short" or "light" wool llamas (by those who didn't care about anything other than fleeced llamas and fiber length, obviously), and even more frequently being insulted as "lesser-quality" by the trend-chasers (in some countries, "zoo llama" has been the term used to degrade and insult the classic llama). The new, dignified (not to mention accurate) term for the traditional, enduring classic-coated llama was an immediate "hit" with classic llama enthusiasts. Today, the term classic llama is in international use and is accepted as the appropriate breed or type name in every English-speaking country.

Predictably, there have been some misunderstandings and misapplications of the term "classic." In an attempt to generate sales, marketers frequently label any shorter-fibered llama as "classic" despite high coat density, near-absence of coarse guard hairs, and/or absence of athletic ability. This is akin to marketing oranges as apples just because piemakers will buy apples to make pies, and why should the seller care what happens after the money changes hands?

Others confuse "classic" with "giant" or "tall" because of the unfortunate name choice of a height registry, the Classic 2000, that listed and promoted llamas by height beginning in 1993. Because the tallest llamas in that registry were considered the elite by the registry owner (and in no small part because "Classic 2000 registered" is a mouthful), the owner, most registry participants, and their acquaintances began referring to their taller-than-average llamas as being classic llamas. However, because the classic llama and the classic coat type had already been recognized and named based on its historic occurence in North American foundation stock, their lazy abbreviation from "Classic 2000 registered llama" to "classic llama" was very unfortunate, and it has caused nothing but confusion and even generated ill-will: After two decades of having their preferred llama type put down by the trendy and woolly marketers, classic llama afficianados are more than a bit sensitive to being slighted, and all attempts to usurp the term "classic" or change the usage (there have been several) have been, understandably, met with strong resistance.

What size is a classic llama, then?

Because "classic" only defines coat type and infers athletic ability, the classic llama can be found in all sizes from tiny to huge and everything in between.

Technically, one could have a classic mini llama, although no one has yet shown interest in such a breed. As a fundamentally working breed, a true classic llama can't be too short or it won't be able to meet the athletic and performance requirements of at least some North American buyers. 42.5" -- well above the maximum height for a mini -- is what most people consider the minimum functional height for classic performance llamas. A minority of classic-coated llamas under 42.5" do possess the requisite athleticism, but in practice, most do not because their size is a byproduct of woolly llama and/or alpaca crossbreeding (the guanaco, progenitor of the classic llama, averages 42.5" in the wild). In addition, all but the smallest humans are reluctant to give smaller llamas the chance to prove themselves athletically.

On the other end of the spectrum, the classic coat type can indeed be found on unusually large llamas as well. Giant or "tall" llamas ("tall" being a very relative term depending on the speaker's own height!) -- especially those llamas 48" and over -- have their own very passionate following. We are not aware of any giant llama breeders who are paying attention to coat type, let alone selecting exclusively for classic coats; it seems that the quest for really tall llamas is hard enough to achieve without introducing other breeding criteria. Of more concern to breeders and users of classic performance llamas is that we and others are noting that the upper limit of optimum size for continued soundness appears to be around 46". That does not mean that all taller llamas won't be sound, but rather that the percentage that break down prematurely begins increasing exponentially for llamas 47" and over. Also, some tall llamas are tall precisely because they have disproportionately long legs, which in turn short-circuits those llamas' potential athleticism. (It is also worth nothing that many llamas' heights are commonly exaggerated by an average of 2" or more. Most people do not take pains to ensure their measurements are precise, and more than a few are prone to "enhancing marketability" by "rounding up" a llama's height. Combine the two and ... well, many "tall" llamas just aren't as tall as is claimed. Many llamas have "shrunk" considerably when we had the opportunity to measure them with the same precision methods we employ on our own llamas.)

If you are wondering about the effects of size on athleticism and long-term soundness, examine older tall llamas, especially working pack llamas, and compare them to similar and older llamas of other sizes who were kept in similar physical condition and who have also been working. All the llamas we're aware of who are still packing into their third decade aren't even close to being tall by anyone's definition!

Or, hit the trail with several over-48" llamas that are tall by virtue of their disproportionately long legs along with some llamas of normal size and proportions. See which llamas step on their own forefeet going uphill or must "crabwalk" or slow down considerably to avoid doing so. Despite statements -- by the "tall" llama promoters, natch -- that llamas under 44" "can't do the job," a high percentage of the very few resoundingly excellent performance llamas -- both classic and other types -- are actually under 44". It's not rocket science! If the loaded llama keeps up with you, s/he's tall enough for you.

(It's also worth noting that many llamas advertised as being a certain height are actually shorter than stated. Sometimes that's because the people who measured the llamas genuinely tried, but were inaccurate; sometimes it's because the "measurement" was actually a guess. And sometimes it's just plain fabrication. Of all the llamas we've measured that were also measured by someone else, not one was as tall as others had said ... often they were actually around 2" shorter, sometimes more. A very fine performance llama measured by someone else at 45" was actually 42.5"; one heavily-advertised stud was not almost 49", but a solid 47"; a supposed 47" stud we purchased is actually 45.5". We use a very precise system on leveled concrete that eliminates quirks of grooming, stance, ground conditions, and desire for a given outcome; no one else we know comes anywhere close to precision in their measuring. So take those "large llama" statements with a grain of salt ... if not a whole salt lick!)

So, to recap: Although the serious classic llama breeders' goal of breeding the most athletic performance llamas with classic coats means that classic llamas are more commonly found in a height range between 42.5 and 46.5", any size llama with the classic coat type is still a classic llama.

What conformational traits are associated with classic llamas?

Again, "classic" only defines coat type and infers athletic ability. There are certain visual qualities common to combed-out classic llamas that are overwhelmingly mistaken as being the breed's conformational attributes (or "shortcomings"). A few examples:

- The combed classic llama's visually trim, almost uniform width compared to leg width and foot placement (rather than the "wide body" look) when viewed from front or rear, a direct result of the classic coat's low density, causes some observers to mistakenly label classic llamas "narrow" or "thin" or "slender" or "lacking substance" (the latter being a common "negative trait" that showring judges use to justify low placements for all classic llamas). A truly narrow-bodied llama doesn't remain stable when loaded with a pack of normal width, especially in rough terrain, so classic llamas selected and bred for performance are definitely not narrow!

- The classic llamas' combination of short rear leg and belly coat results in exposure of the normal abdominal contour, a trait common to all llamas (this seems high in comparison to other domestic livestock because the entire camelid family lacks an inguinal fold). The visibility of this trait causes observers to mistakenly label classic llamas as being "tucked up in the belly [or groin]" or "high-flanked" in comparison to other llamas. However, except for llamas who are quite obese (thus lowering the visual bottom line of the abdomen), this contour is in fact common to ALL llamas and definitely is not tied to any breeed, coat or fleece type.

- The lack of undercoat at the tailhead produces the visual effect of a rounding of the rump just before the root of the tail; a slight wither contour may also be barely discernable (instead of the "flat back" look of fleeced llamas); this comformational aspect is again common to all llamas. However, it is common for ignorant observers (including most judges) to refer to these well-groomed, true classic llamas as having "poor toplines" or "low tailsets". Disappointed breeders who put ribbons over performance may then crossbreed their wonderful and properly-conformed classics to light-wool llamas in hopes of "improving the topline" and, in the process, destroy the valuable classic coat in as little as a single generation.

As you have probably surmised, visual appearance, shows, and comparison to woolly llamas are far and away the primary influencing factors in misinterpretation of conformational traits in classic llamas. Independent of coat type, obesity and inappropriate management (such as immature breeding) also cause a substantial amount of misinterpretation of conformation in all llamas.

Another problem in defining conformational traits in classic llamas is that ego and personal opinion (the latter often being proffered without thorough research and/or as the outgrowth of personal prejudice) play a heavy role within individual breeding programs. Additionally, as will be expected by anyone familiar with human nature and animal breeding, quite a few people who breed classic llamas emphasize (or even overemphasize) a few traits (or even a single trait) because that's a good deal easier than paying careful attention to the rather complicated whole. In either case, the result is that many people make breeding choices based on personal opinion instead of objectively-measured function, resulting in less-than-optimal performance in order to exaggerate the observable traits that the individual breeder is infatuated with. Another result of these approaches is that the classic coat type gets de-emphasized and even lost when breeders place extremes of other traits above all else.

Then there's the education gap. More than a few classic llama breeders think they know what effect a particular physical trait has on function, but as the following common example shows, they can't all be correct: One breeder declares that a deep chest is critical to a good pack llama; another breeder insists that a shallow chest is paramount for a good pack llama (these are not hypothetical examples!). Both can't be correct! In some cases of obvious contradiciton, the trait being focusing on is of minimal importance; in others (as is more likely in this case), it is once again an example of the trait being assessed visually and thus incorrectly, as when a llama who has a shorn underside is declared to have a "shallow chest" and the very same llama with normal coat growth hanging from the sternum is perceived as having a "deep chest".

Regardless of disagreement over conformational specifics and differing opinions on the importance of specific conformational traits, the resulting llamas are still classic llamas as long as they exhibit the combable classic coat type -- it's just that some may not be good classic llamas for performance purposes.

Why not produce "all purpose" llamas?

From the beginning of recorded history, humans have tried and failed to produce all-purpose breeds in every species of domestic animal. The failures do not come from a lack of breeding skills or the necessity for additional generations of selection -- the failures are entirely because what is required for excellence in one area conflicts with the requirements for excellence (or even adequacy) in another. When excellence is required, only a specialist breed can meet human needs. Even in wild animals, extremes of many traits do not exist in order to produce a viable whole that can survive.

Both packing and driving are not easy for the average llama, so a breed selected for these abilities is necessary if human needs are to be met -- it is necessary for llamas to excel in these areas compared to the majority of the species merely to be deemed suitable! The athletic body type required as well as some of the biomechanical tradeoffs necessary for excellent performance conflict with wool production needs, halter class fashion, and (only an issue in South America) meat production. More importantly, the overall coat type necessary for a llama to perform suitably is in complete opposition to the characteristics required for acceptable (let alone desirable) fiber production and quality. The South Americans had the right idea -- two kinds of llamas -- it's just that some North Americans seem to have to learn it the hard way. It is worth mentioning that the strongest proponents of "all-purpose" llamas are people breed llamas that are not suited to any particular purpose at all.

Why is the coat type so important for a performance llama?

Anyone with minimal experience will agree that performance is affected by the body. Llamas are different than many of our other working domestic animals -- they have a unique type of fiber coverage, which is necessary to protect them from harsh weather of all kinds.

Both the guanaco progenitors and the classic llamas have short, slick-haired undersides and bodies covered with a coat consisting of two distinct fiber types: a soft, short, and very fine wool fiber; and a coarse, long and very thick guard hair fiber (woolly llamas have been selected for a single-fiber coat). Two features of the coat can afford adequate weather protection: wool fiber density, and guard hair quantity and coverage. The working llama cannot afford to have dense fiber -- even if it is short -- because it retains heat. Abundant guard hairs, however, provide all the weather protection necessary while still allowing adequate heat dispersal. Abundant guard hair also promotes ease of combing (which maintains coat sparsity) by preventing the tips of the undercoat from felting together.

Another coat type problem for the performance llama is a genetic factor that increases the amount of the llama's undersurface covered by the heavier body coat, referred to as wool encroachment. This simple recessive factor is closely allied with wool fiber length and density, but may appear alone on a llama that otherwise appears to be a true classic type. Llamas expressing this phenotype have slick-haired regions only on their armpits, a small area of their chest, and a much-reduced patch in the inguinal region. This translates directly to temperature regulation difficulties, even when at rest in a pasture.

Why not just shear a woollier llama?

Shearing does not reduce coat density. In order to compensate for density and allow heat dispersal under working conditions, a llama's fiber must be shorn to less than 1" AND thinned to remove more fiber. However, controlled temperature regulation studies have determined that fleece must be both dense (unthinned) and at least 2" -- twice the length that permits cooling -- is necessary for weather protection in the backcountry. In other words, if a woollier llama has been shorn close enough to adequately disperse heat while working, even a "raincoat" won't provide a him or her with the warmth s/he needs on the trail if the weather unexpectedly turns nasty. A driving llama, returned home under the same conditions, may need to be stalled and warmed to avoid compromise. Certainly, even though these llamas may be used for low- to mid-level performance duty after significant human intervention, they can hardly be termed superior or "good quality" performance llamas.

Wool encroachment is more easily addressed because the affected regions can be protected from the weather when the llama kushes. The unwanted belly fiber can be shaved off at skin level several times during the packing or driving season. However, it is the goal of most classic llama breeders to select against wool encroachment.

Are classic llamas "living relics"? Is "classic" the same as "ccara"?

The short answer is "no". Those who breed classic llamas for performance certainly are interested in recovering and selecting for the best performance traits available in the llama gene pool. However, what was acceptable for the South Americans centuries ago won't necessarily turn out to be the best we can breed for modern use in North America. That's why the classic performance llama breeders don't claim to be breeding ccara llamas -- that would bind them to whatever the current North American understanding of "ccara" is (which definitely includes light wool; one faction says "ccara" means giant or tall llamas exclusively). Instead, they choose to pursue the traditional and enduring criteria of breeding the best possible working llamas with the specific trait of the classic coat.

One obvious manifestation of the difference between the modern North American Classic Llamas and ccara llamas is climate tolerance. In South America, llamas remained in a single region and rarely were required to work in a different climate. When they were, the difference was minor. So some of the ccara llamas could afford to be denser fibered in some geographical areas and sparser in others. In North America, a recreational llama packer may live in western Oregon (where the winters are very wet, springs humid, and summers dry and warm) and yet choose to take a season's pack trips into such diverse areas as Washington's North Cascades (where the weather never stays "good," often gets quite nasty, and can snow at any time), the Great Basin region (where it gets d***ed hot during the day and may freeze any night of the year), and literally anywhere in between. A pack llama in North America is not much use unless his or her performance shines in these radically different climates without compromising health or requiring time to readjust.

Another distinct difference between modern North American demands on the classic llama and South American demands on their ccara llamas is working pace. The South American handlers are shorter and move at a leisurely pace; the animals graze and meander as they travel. The best looking, not the best working, are selected for breeding (castrations are done before the llamas reach working age). In North America, the llama must be able to match and maintain the pace of the North American human handler, sometimes day after day. This is a significant and difficult demand on the llama as a species -- one that can only be met through stringent selective breeding practices.

Yet another significant difference is the different relationship North Americans have with their working llamas. South American llamas travel in herds and relate to other llamas, not individual humans. Although strings of llamas are employed by commercial packers and work crews in North America, there are many more llamas packing for private individuals. These individuals (as well as a significant percentage of the commercial packers' clientele) desire a relationship with their llamas. Some hikers travel alone; some may travel with others but wish to explore an alternate route or take a day hike alone. A trail work crew may need to split up. The herd-bound llama who becomes hysterical upon separation from his or her kind is of no consequence in South America, but may be unusable -- even dangerous -- under these circumstances. Both facets -- willingness and desire to relate to humans, and adequate independence from conspecifics -- are inherited personality characteristics that are not universal within the llama gene pool. Again, selective breeding is the answer.

Perhaps the most obvious differences between North and South American llamas are uses secondary to packing. Some of the South American peasants must use wool from all their llamas, regardless of quality, and make breeding choices accordingly. All South Americans eat llama meat at one time or another, which also affects breeding choices. In North America, we have access to far superior synthetic and natural fibers (including alpaca and woolly llama), and also to vastly superior meat sources. We, as a culture, make a distinction between "companion animals" (that we don't eat) and "meat animals" (that we don't keep as companions), and this distinction runs along species lines. On the other hand, we ask our performance llamas to drive, perform advanced training exercises, compete over obstacles, and even compete at halter. Halter competition adds aesthetic criteria; training and performance competition both add significant mental demands; and driving adds mental, emotional, and stringent physical requirements. Some of the necessary traits for these uses are counter to the traits desirable for South American uses. So it is not enough to merely breed a ccara llama. Instead, the demands of North American llama owners require that breeders place emphasis on different and more specific selection criteria.

I don't see Classic llamas in shows!

Yep, that's right. It used to be that Classic llamas had to be shown in the "LIGHTWOOL" division (or worse still, a combined "light and medium wool" division). For a fleeting time, there was a separate Classic llama division, but in some areas it wasn't offered and in others, people with the lighter-woolled crossbreds entered their llamas in "Classic". Some judges removed them; others gave them top placings. Now the trend in most parts of the country is combined Classic coat and Light Wool, with the Classic llamas rarely entered -- it's expensive to pay for transport, stalls, and entries only to be placed last because they are then judged in the mixed classes partially as potential fiber producers: on fiber softness, pasture soundness only, and aesthetic appeal. Partial shearing is common among the dense-wooled and crossbred class entries (if it has to be shorn, you can be certain that it's NOT a classic llama!), combed classics are invariably described as "lacking substance" (remember, the coat's lack of loft results in a slimmer visual outline), and the highest-placing animals are often praised for their presence or eye appeal (despite the fact that they may be physically unsuitable for packing or driving).

Further compounding old prejudices, showring judges also continues to reflect the damaging, non-user generated and perpetuated beliefs that "leftover llamas are for packing," "big llamas are better packers," and that not only is there such a thing as an all-purpose (wool and pack) llama, but that all llamas shown at halter should be held to that unachievable goal. Of course the latter translates to the largest, wooliest llama (remember, the judges largely believe that big equals better packing performance). What a frustration for the dedicated classic performance llama breeder who has struggled to produce llamas that actually do excel at packing and driving in the real world!

You might wonder why anyone would show a classic llama at halter under the present circumstances. We certainly wondered with great regularity! Our reason for doing so was not for recognition (in fact, we now question the suitability of any Classic OR working llama for breeding if it consistantly places well at halter), but rather to keep the increasingly rare classic-coated, high-performance llamas visible to current and future performance llama users. From the amount of attention we attracted outside the showring, it's clear that there are many people who are enthusiastic about high-performance Classic llamas despite the show organizations' continuing refusal to recognize working qualities or reward this re-emerging breed's defining characteristics completely separate from fiber producers and crossbreds.

Of course, the many years of refusal to recognize classic llamas is probably a huge blessing in disguise. Now that there's a halter class category for classic llamas, a breed split is predictably occurring: A show-only sub-type bred to nonfunctional beauty standards, and a working sub-type that doesn't place well in halter classes (because halter judges reward a number of physical traits detrimental to performance and penalize several attributes that figure heavily into superior performance). This split has occurred in every single working breed of domestic animal, and if anything, llama showing and judging is more artificially-determined than that of horses and dogs.

After the arrival of the Spanish in South America, the native breeding programs for lamas were badly disrupted or destroyed. Since that time, crossbreeding of types -- even of llamas with alpacas -- has been common, and the South American ccara llamas today frequently show one or more telltale signs of this crossbreeding in their phenotype.

Most of the classic llamas in North America, derived originally from the crossbred South American gene pool, still do not breed true-to-type. This has unfortunately been exacerbated because of an emphasis on crossbreeding classic llamas to woolly llamas in this country, both with the expectation of higher profit ("more wool" -- regardless of quality -- used to automatically bring more money) and under the misguided notion that densely-wooled llamas are actually as large as their fleeces make them appear.

As a result, a significant number of classic-appearing llamas do not have molting, combable coats despite having short fiber, and many do not possess the stamina, strength, and athletic ability required to pack or drive acceptably. Even fewer excel. If there was a truly purebred, traditional working llama at one time (that is, a population that always bred true-to-type), that gene pool has been irrevocably scattered throughout the llama population on both continents. However, the growing number of people interested in recovering the superior performance and practical coat type of the traditional llama as well as using selective breeding to better adapt succeeding generations to modern uses bodes well for the future of the North American Classic Llama.

To see more examples of the classic llama phenotype, visit the breeding and prospective breeding members of our llama family.

Or, email to coordinate a farm visit for an invaluable, hands-on experience -- in recent years, our experience is that many people have seen short-wooled llamas, but have never actually encountered any true classic-coated llamas.

Return to Lost Creek Llamas home page